Dyspepsia

At a Glance

How It Affects You

Dyspepsia, commonly known as indigestion, primarily affects the upper digestive tract, causing distinct discomfort or pain in the upper abdomen. This condition involves the stomach and the beginning of the small intestine, leading to sensations that interfere with the comfortable digestion of food. The physical effects can range from mild annoyance to significant discomfort that disrupts daily eating habits.

- It causes a persistent or recurrent burning sensation or gnawing pain in the area between the navel and the lower ribs.

- It leads to a feeling of uncomfortable fullness during or immediately after a meal, often resulting in the inability to finish a normal-sized portion.

- It frequently produces bothersome bloating, excessive gas, and nausea that may occur independently of hunger levels.

Causes and Risk Factors

Underlying Causes and Biological Mechanisms

Dyspepsia can stem from identifiable structural problems or functional issues where the digestive tract appears normal but fails to function properly. Functional dyspepsia is the most common form, where nerves in the stomach may be hypersensitive to expansion, or the stomach may not empty as quickly as it should. Other direct causes include peptic ulcers, which are sores in the lining of the stomach or small intestine, and inflammation of the stomach lining known as gastritis. Infection with Helicobacter pylori bacteria is a frequent contributor to inflammation and ulceration. In some cases, structural diseases such as acid reflux, gallbladder disorders, or rare metabolic conditions can present with dyspeptic symptoms.

Risk Factors and Triggers

Various lifestyle and environmental factors can trigger or worsen symptoms. Consuming large, fatty, or spicy meals often exacerbates discomfort, as does eating too quickly. Beverages containing caffeine, alcohol, or carbonation are common triggers. Smoking tobacco is a significant risk factor because it alters stomach acid production and relaxes the valve between the esophagus and stomach. Certain medications are also well-known contributors; non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as aspirin and ibuprofen, can irritate the stomach lining and cause indigestion. Emotional stress and anxiety may amplify symptoms through the gut-brain axis.

Prevention Strategies

Primary prevention involves adopting habits that support healthy digestion. Maintaining a healthy weight reduces pressure on the abdomen, which can help alleviate symptoms. Avoiding known dietary triggers and eating smaller, more frequent meals rather than three large ones can prevent the stomach from becoming overly full. Stopping smoking is a crucial step for preventing chronic digestive issues. While it is not always possible to prevent functional dyspepsia entirely due to its complex biological nature, minimizing the use of NSAIDs or taking them with food can reduce the risk of drug-induced indigestion.

Diagnosis, Signs, and Symptoms

Signs and Symptoms

The hallmark symptom of dyspepsia is pain or discomfort centered in the upper abdomen, often described as a burning or gnawing sensation. Patients frequently report early satiety, which is feeling full soon after starting a meal, preventing them from finishing normal portions. Postprandial fullness, an uncomfortable sensation of food prolonged in the stomach, is also common. Other symptoms include bloating, nausea, and excessive belching. These symptoms can vary in intensity and may come and go over time. It is important to note that while heartburn (a burning feeling moving up the chest) can coexist with dyspepsia, dyspepsia specifically refers to epigastric (upper abdominal) pain rather than retrosternal (chest) pain.

Diagnostic Process

Clinicians identify dyspepsia primarily through a detailed medical history and physical examination to locate the pain and identify potential triggers. To distinguish between functional dyspepsia and structural causes, doctors may check for Helicobacter pylori infection using a breath test, stool antigen test, or blood test. Routine blood work may be ordered to rule out anemia or metabolic disorders. In patients over a certain age (often 60) or those with alarming symptoms, an upper endoscopy (EGD) is typically performed. This involves passing a flexible camera down the throat to visually inspect the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum for ulcers, inflammation, or masses.

Differential Diagnosis

Dyspepsia is often confused with other gastrointestinal disorders due to overlapping symptoms. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is the most common differential, distinguished by predominant heartburn and acid regurgitation. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) may also present with abdominal pain, but IBS is usually associated with changes in bowel habits like diarrhea or constipation. Less commonly, symptoms may mimic biliary colic from gallstones, pancreatitis, or even cardiac issues like angina, which is why a thorough evaluation is essential.

Treatment and Management

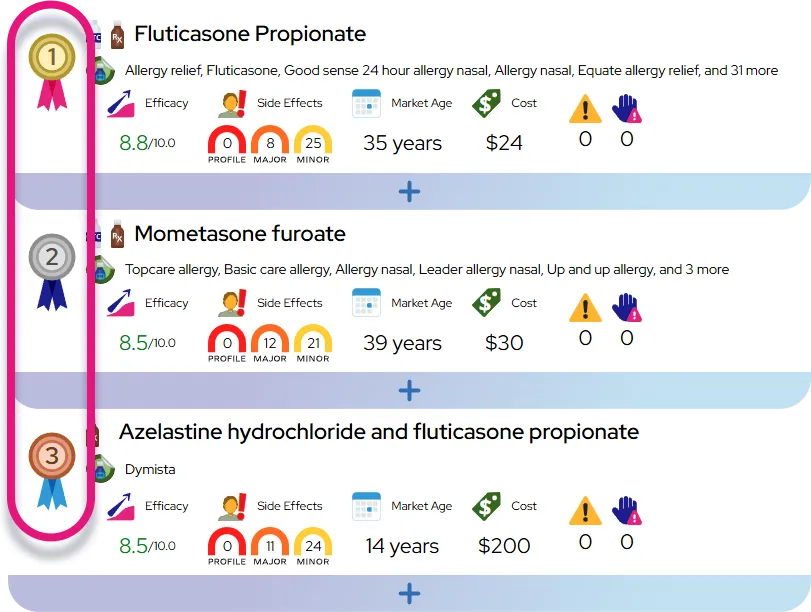

Medications

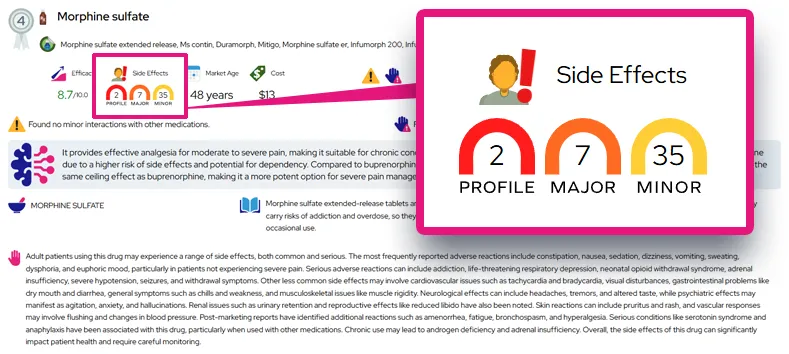

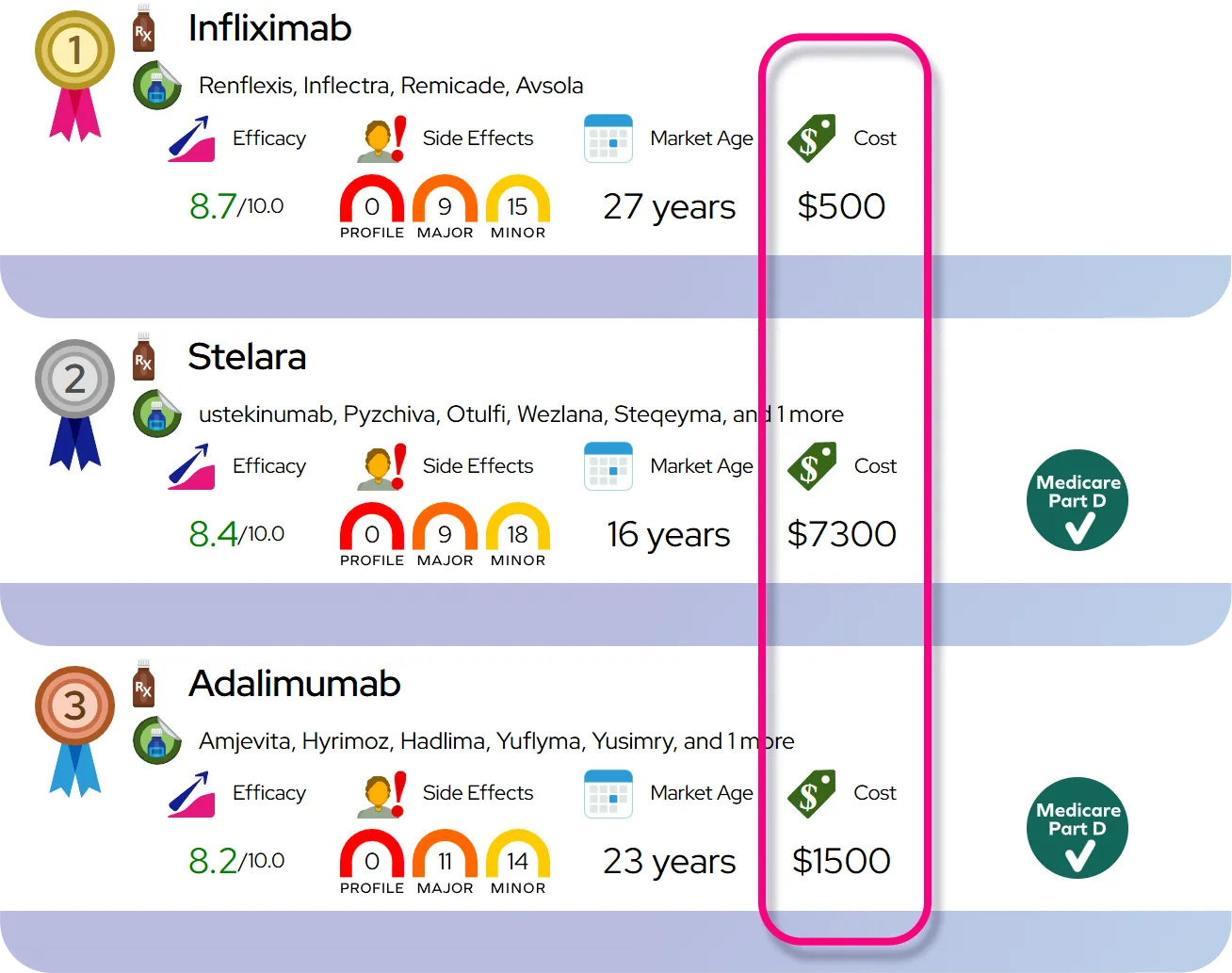

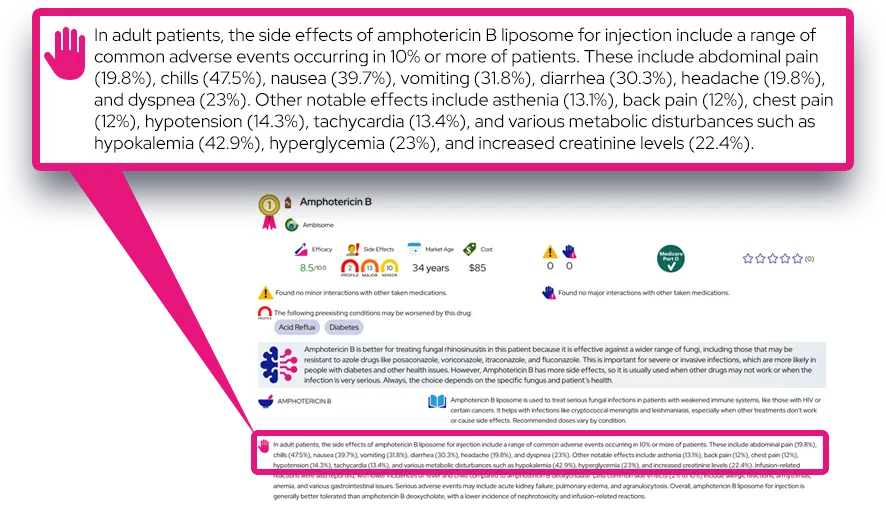

Treatment often begins with medications to reduce stomach acid or improve motility. Over-the-counter antacids provide rapid, short-term relief by neutralizing acid. Histamine-2 (H2) blockers reduce acid production and offer longer relief. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are the most potent acid suppressants and are commonly prescribed for frequent symptoms or when ulcers are present. If Helicobacter pylori infection is detected, a course of antibiotics combined with acid suppression is necessary to eradicate the bacteria. For functional dyspepsia specifically, prokinetic agents may be used to help the stomach empty faster, and low-dose tricyclic antidepressants are sometimes prescribed to modulate nerve sensitivity in the gut.

Lifestyle and Self-Care

Lifestyle modifications are foundational to managing dyspepsia. Patients are encouraged to identify and avoid personal food triggers, which may include fatty foods, chocolate, mint, or citrus. Eating slowly and chewing food thoroughly can reduce the workload on the stomach. Avoiding late-night eating helps prevent symptoms before sleep. Stress management techniques, such as relaxation therapy or cognitive behavioral therapy, can be effective, particularly when symptoms are linked to emotional distress.

When to See a Doctor

While mild indigestion is common, certain signs require immediate medical attention. A healthcare provider should be consulted if symptoms persist despite lifestyle changes or over-the-counter treatment. Immediate care is needed if any "alarm features" develop.

- Unintentional or unexplained weight loss.

- Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) or painful swallowing.

- Persistent vomiting or vomiting blood.

- Black, tarry, or bloody stools.

- Severe abdominal pain or a palpable mass in the abdomen.

- Unexplained anemia (low red blood cell count).

Severity and Prognosis

Severity and Complications

Dyspepsia is generally considered a mild to moderate condition, but severe cases can significantly impact daily functioning. Functional dyspepsia does not lead to life-threatening complications like cancer, but it can cause considerable distress and disrupt sleep and work. When dyspepsia is caused by peptic ulcers, complications can include bleeding or perforation of the stomach wall if left untreated. Chronic inflammation from conditions associated with dyspepsia can sometimes lead to scarring or narrowing of the digestive tract, known as strictures, which may impede the passage of food.

Prognosis and Disease Course

The course of dyspepsia is often chronic and fluctuating, with periods of remission followed by symptom flare-ups. For those with functional dyspepsia, symptoms may persist for years but do not worsen the risk of mortality. If the underlying cause is identified and treated—such as eradicating H. pylori or healing an ulcer—symptoms often resolve permanently. However, many patients require intermittent or long-term management strategies. Early diagnosis and adherence to treatment plans generally lead to better symptom control and a reduction in the recurrence of discomfort.

Impact on Daily Life

Impact on Daily Activities

Living with dyspepsia can affect enjoyment of food and social interactions. Patients may feel anxious about eating in restaurants or social gatherings due to fear of triggering symptoms. The discomfort can be distracting, potentially reducing productivity at work or school. Fatigue may occur if symptoms disrupt sleep. Practical coping strategies include keeping a food diary to pinpoint triggers, eating small snacks instead of large meals, and wearing loose-fitting clothing to avoid pressure on the abdomen. Support from dietitians can help maintain proper nutrition without aggravating the stomach.

Questions to Ask Your Healthcare Provider

Being prepared for appointments can help patients better manage their condition. The following questions are useful for understanding the diagnosis and treatment plan:

- What is the most likely cause of my symptoms?

- Do I need to be tested for H. pylori or other underlying conditions?

- Are there specific foods or drinks I should completely eliminate?

- What are the potential side effects of the medications you are prescribing?

- How long should I take this medication, and can I stop it abruptly?

- Should I schedule a follow-up appointment or an endoscopy?

- Are there any warning signs that should prompt me to seek emergency care?

Common Questions and Answers

Q: Is indigestion the same thing as heartburn?

A: No, although they often happen together. Indigestion (dyspepsia) refers to pain or fullness in the upper abdomen, while heartburn is a burning sensation that moves up the chest towards the throat, caused by acid reflux.

Q: Can stress cause dyspepsia?

A: Yes, stress and anxiety can significantly affect the digestive system. The brain and gut are closely connected, so emotional stress can increase stomach sensitivity or slow down digestion, triggering symptoms.

Q: Will drinking milk help soothe my stomach pain?

A: Milk might provide temporary relief by coating the stomach, but it can sometimes make symptoms worse later. Milk stimulates the stomach to produce more acid, and if you are lactose intolerant, it can cause additional bloating and gas.

Q: Is dyspepsia a sign of stomach cancer?

A: Dyspepsia is extremely common and is rarely a sign of cancer. However, if you have new symptoms after age 60, lose weight without trying, or have trouble swallowing, doctors will investigate further to rule out serious conditions.

Q: Can I cure functional dyspepsia permanently?

A: Functional dyspepsia is often a chronic condition that comes and goes. While there may not be a single permanent cure, most people can successfully control symptoms and prevent flare-ups through diet, lifestyle changes, and medication.