Non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis

At a Glance

How It Affects You

Non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis primarily impacts the lungs, where the bronchial tubes become permanently widened and thickened due to chronic inflammation and infection. This structural damage prevents the airways from clearing mucus effectively, creating an environment where bacteria can easily grow and cause repeated lung infections. Over time, this cycle of infection and inflammation can lead to progressive scarring and reduced lung function, affecting the body's ability to oxygenate blood efficiently.The condition specifically leads to the following physiological changes:

- Accumulation of thick, sticky mucus in the dilated airways that is difficult to cough up.

- Recurrent cycles of respiratory infections that further damage lung tissue.

- Reduced airflow and gas exchange, potentially leading to shortness of breath and fatigue.

Causes and Risk Factors

Underlying Causes and Mechanisms

Non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis is caused by a cycle of inflammation and infection that permanently damages the bronchial walls. In many cases, the exact cause is never identified, a classification known as idiopathic bronchiectasis. When a cause is found, it often stems from a past severe lung infection, such as pneumonia, tuberculosis, or whooping cough, which scars the airways. Other significant contributors include immune system deficiencies that make the body unable to fight off respiratory bacteria, and autoimmune conditions like rheumatoid arthritis or Sjogren's syndrome. Structural issues within the lung, such as a blockage from a foreign object or a growth, can also lead to localized bronchiectasis. Genetic disorders affecting the cilia (tiny hair-like structures that clear mucus), such as primary ciliary dyskinesia, are less common but recognized causes.

Risk Factors

Several factors increase the likelihood of developing this condition. A history of severe or recurrent respiratory infections in childhood is a major risk factor. Individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma are at higher risk, particularly if their condition is poorly controlled. Age and biological sex play a role, with older women being the most frequently affected demographic. Additionally, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) may contribute to airway damage through the aspiration of stomach acid into the lungs.

Prevention Strategies

Primary prevention focuses on protecting the lungs from initial damage. This includes staying up to date with vaccinations against influenza, pneumonia (pneumococcal), and pertussis (whooping cough) to prevent severe respiratory infections. Treating underlying conditions promptly, such as effectively managing asthma or autoimmune disorders, can help preserve lung integrity. For those who smoke, quitting is essential to prevent further airway irritation and damage. While not all cases are preventable, particularly those with genetic origins, early diagnosis and management of respiratory illnesses can significantly reduce the risk of developing severe airway dilation.

Diagnosis, Signs, and Symptoms

Signs and Symptoms

The hallmark symptom of non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis is a persistent, chronic cough that produces significant amounts of mucus (sputum) daily. This mucus may be clear, pale yellow, or greenish, and its consistency can vary. Patients often experience recurrent chest infections that take a long time to clear up. Other common symptoms include shortness of breath (especially during physical activity), extreme fatigue, chest pain, and wheezing. In some cases, individuals may cough up blood (hemoptysis), which indicates fragile blood vessels in the damaged airways. Symptoms can fluctuate, with periods of relative stability interrupted by "exacerbations" or flare-ups where cough and mucus production worsen significantly.

Diagnostic Tests and Exams

Clinicians typically suspect bronchiectasis based on a patient's history of chronic cough and repeated infections. The gold standard for confirming the diagnosis is a High-Resolution Computed Tomography (HRCT) scan of the chest. Unlike a standard chest X-ray, an HRCT provides detailed cross-sectional images of the lungs, revealing the characteristic widened and thickened airways. To identify the specific bacteria causing infections, doctors frequently collect sputum samples for culture. Pulmonary function tests (spirometry) are used to measure how well the lungs move air in and out, assessing the severity of airflow obstruction. Bronchoscopy, a procedure where a camera is passed into the lungs, may be used in specific cases to locate blockages or obtain deeper tissue samples.

Differential Diagnosis

Because the symptoms overlap with other respiratory diseases, non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis is often confused with conditions like Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), chronic bronchitis, or asthma. It is distinguished from cystic fibrosis (CF) through genetic testing or a sweat chloride test; a negative result for CF is required to classify the condition as "non-cystic fibrosis" bronchiectasis.

Treatment and Management

Airway Clearance Techniques

The cornerstone of management is keeping the lungs clear of mucus to prevent infection. Physical therapy techniques are used daily to help mobilize secretions. This often involves the Active Cycle of Breathing Techniques (ACBT) or postural drainage, where gravity helps drain mucus from the lungs. Handheld oscillatory positive expiratory pressure (PEP) devices are also commonly prescribed; these devices create vibrations in the airways when a patient breathes into them, helping to loosen sticky mucus so it can be coughed out effectively.

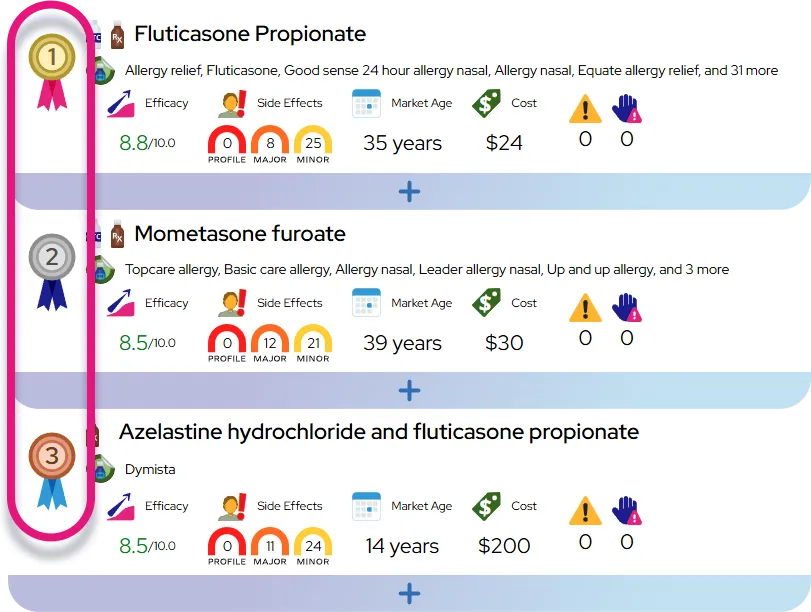

Medications

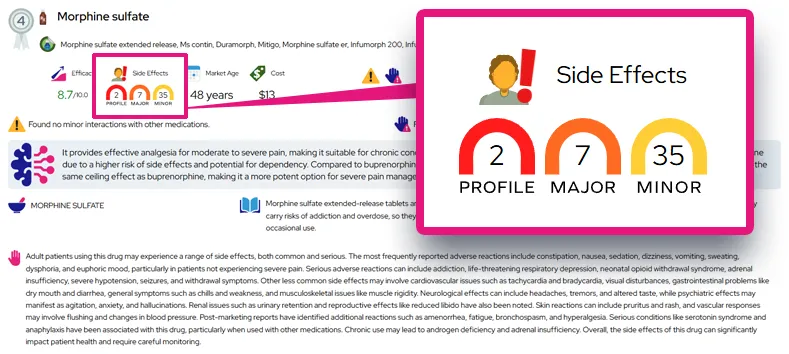

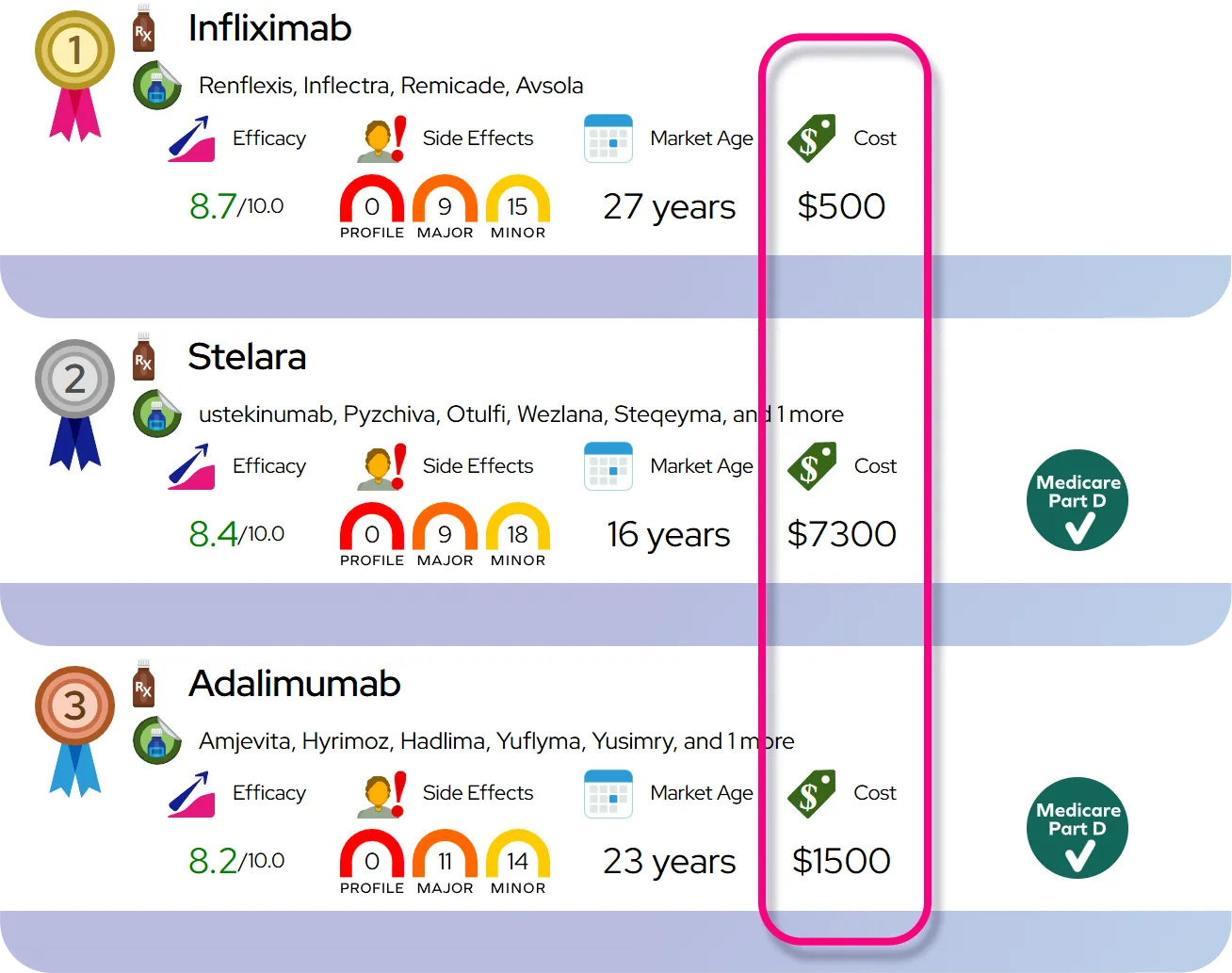

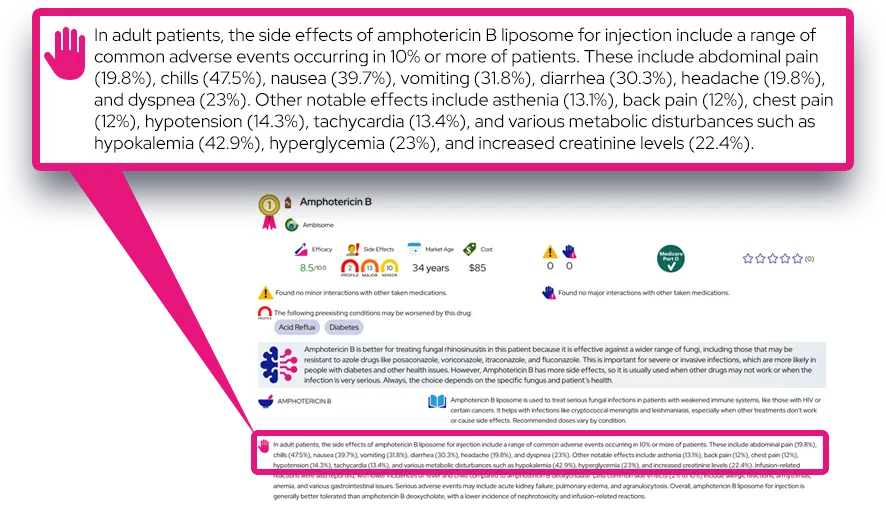

Medical treatment aims to treat infections and reduce inflammation. Antibiotics are the primary defense against bacterial flare-ups and may be given orally or intravenously depending on severity. In some cases, inhaled antibiotics are used long-term to suppress chronic bacterial presence (such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa) without systemic side effects. Mucolytics, such as nebulized hypertonic saline, may be prescribed to thin the mucus, making it easier to expel. Bronchodilators can help relax the airway muscles if there is associated airflow obstruction or asthma. Unlike in asthma, inhaled corticosteroids are generally reserved for patients who also have significant airway inflammation or overlapping conditions.

Lifestyle and Self-Care

Regular exercise is highly beneficial as it naturally helps loosen mucus and improves overall cardiovascular fitness. Staying well-hydrated is also important to keep mucus less sticky. Patients are strongly advised to avoid lung irritants, including cigarette smoke and pollution. An annual flu shot and periodic pneumonia vaccines are critical parts of self-care to avoid dangerous complications.

When to Seek Medical Care

Patients should establish a clear action plan with their doctor. Routine follow-up is typically needed every 6 to 12 months to monitor lung function. Immediate medical attention should be sought if there are signs of a severe exacerbation, such as a high fever, chest pain, or a sudden increase in shortness of breath. Coughing up significant amounts of fresh blood (more than a few teaspoons) is a red flag that requires emergency evaluation. If symptoms of a chest infection do not improve after starting antibiotics, patients should contact their healthcare provider promptly.

Severity and Prognosis

Severity Levels

The severity of non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis varies widely among individuals. Some people have mild disease with only occasional cough and rare infections, while others experience frequent, severe exacerbations that require hospitalization. Clinicians often use scoring systems (like the Bronchiectasis Severity Index) that consider age, body mass index, lung function, and infection history to classify the disease as mild, moderate, or severe. Factors that worsen the prognosis include advanced age, infection with resistant bacteria like Pseudomonas, and the presence of other conditions such as COPD.

Disease Course and Complications

The condition is generally progressive, meaning lung damage can accumulate over time if not aggressively managed. However, with modern treatment, many patients achieve long periods of stability. The most common complication is recurrent pneumonia or acute exacerbations. Long-term complications can include respiratory failure, where oxygen levels in the blood become chronically low, requiring supplemental oxygen. Chronic inflammation can also strain the heart, potentially leading to heart failure (cor pulmonale) in very advanced stages.

Life Expectancy and Prognosis

For the majority of patients with mild to moderate disease, life expectancy is comparable to the general population. The outlook has improved significantly with better antibiotics and airway clearance protocols. Mortality is typically related to severe respiratory failure or cardiovascular complications in those with advanced disease. Early diagnosis and adherence to physiotherapy and treatment regimens are the strongest predictors of a positive outcome, effectively slowing the rate of lung decline.

Impact on Daily Life

Daily Activities and Social Life

Living with bronchiectasis requires a commitment to a daily routine, which can be time-consuming. Patients typically need to dedicate 20 to 40 minutes once or twice a day to airway clearance exercises. The chronic cough can be physically exhausting and socially embarrassing, sometimes leading to isolation or anxiety about being in quiet public spaces (like theaters or meetings). Fatigue is a common complaint that may limit the ability to participate in strenuous activities or work full-time without adjustments.

Mental and Emotional Health

The unpredictable nature of flare-ups can cause anxiety, particularly regarding travel or planning future events. Coping strategies include joining support groups where patients can share experiences and tips. Learning effective cough suppression techniques for social situations and maintaining open communication with friends and family about the nature of the condition can help reduce social stigma.

Questions to Ask Your Healthcare Provider

Being prepared for appointments helps ensure you get the best care. Consider asking the following questions:

- What is the specific underlying cause of my bronchiectasis, or is it idiopathic?

- How often should I perform airway clearance, and which technique is best for me?

- Am I a candidate for a nebulizer or inhaled antibiotics?

- What specific signs indicate I am having a flare-up and need to start my emergency antibiotics?

- Are there any specific vaccines I need right now?

- Can you refer me to a pulmonary rehabilitation program to help with exercise?

Common Questions and Answers

Q: Is non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis contagious?

A: No, the condition itself is not contagious. However, the bacteria or viruses causing an active infection during a flare-up can be spread to others, so standard hygiene practices like hand washing are important.

Q: Can the lung damage be reversed?

A: Generally, the dilation and scarring of the airways are permanent and cannot be reversed. Treatment focuses on preventing further damage and managing symptoms rather than repairing the existing structural changes.

Q: Is this condition a form of lung cancer?

A: No, bronchiectasis is not cancer. It is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways. However, chronic inflammation is a general stressor on the body, so maintaining overall health is important.

Q: will I need surgery for this condition?

A: Surgery is rarely needed and is considered a last resort. It is typically reserved for patients who have localized damage in just one part of the lung that causes severe, uncontrollable bleeding or infections despite maximum medical treatment.

Q: Can I still exercise if I have bronchiectasis?

A: Yes, exercise is highly encouraged. Physical activity helps loosen mucus, strengthens the chest muscles, and improves overall lung capacity. Patients should consult their doctor to create a safe exercise plan.