Urticaria

At a Glance

How It Affects You

Urticaria, commonly known as hives, manifests as raised, itchy welts (wheals) on the skin that can vary in size and appear anywhere on the body. These welts are caused by the release of histamine and other inflammatory chemicals from mast cells, leading to fluid leaking into the surrounding tissue. The condition often presents with the following characteristics:

- Red or skin-colored elevations that blanch (turn white) when pressed.

- Intense itching, stinging, or burning sensations.

- Potential accompanying swelling (angioedema) in deeper tissue layers, often affecting the lips, eyelids, hands, or feet.

Causes and Risk Factors

Biological Mechanisms and Causes

Urticaria is primarily caused by the degranulation of mast cells in the skin, which releases histamine and other inflammatory mediators. This release causes blood vessels to leak fluid, resulting in the characteristic swelling and redness. In acute cases, this reaction is often triggered by an external factor. Common causes include allergic reactions to foods (such as nuts, shellfish, eggs, or milk), medications (particularly antibiotics like penicillin and aspirin), and insect stings. Infections are another frequent cause; viral infections (like the common cold) and bacterial infections can provoke hives, especially in children. In chronic cases, the cause is often harder to identify. Many chronic cases are autoimmune in nature, where the body's immune system mistakenly attacks its own tissues, while others are "idiopathic," meaning the exact cause remains unknown. Physical stimuli such as cold, heat, pressure on the skin, sunlight, vibration, or exercise (sweating) can also induce specific types of urticaria.

Risk Factors

Certain factors increase the likelihood of developing urticaria. A personal or family history of allergies, eczema, or asthma can elevate risk. Individuals with existing autoimmune disorders, such as thyroid disease or type 1 diabetes, are more prone to chronic forms of the condition. Stress and emotional distress are known to worsen symptoms or trigger flare-ups in susceptible individuals. Recent illnesses, blood transfusions, or exposure to certain chemicals can also act as risk factors.

Prevention

Primary prevention involves identifying and avoiding known triggers. If a specific food, medication, or environmental factor is confirmed as a cause, strict avoidance is the most effective strategy. For physical urticaria, avoiding the specific stimulus (such as wearing loose clothing to avoid pressure or using lukewarm water to avoid temperature extremes) is key. Secondary prevention aims to reduce the frequency and severity of flare-ups. This often involves taking prescribed antihistamines daily rather than just when symptoms appear, particularly for chronic cases. Managing stress through relaxation techniques and maintaining a healthy lifestyle can also help reduce the burden of the disease. Currently, there is no vaccine to prevent urticaria, and since many cases are idiopathic or spontaneous, total prevention is not always possible.

Diagnosis, Signs, and Symptoms

Signs and Symptoms

The hallmark symptom of urticaria is the appearance of wheals—raised, pink or red swellings on the skin. These welts can range in size from pinpoints to large plates and may change shape, move around, or disappear and reappear within hours. The central area of the welt often blanches (turns white) when pressed. The most prominent sensation is intense itching, which can be severe enough to disrupt sleep or daily activities. Some individuals also experience a burning or stinging sensation. About 40% of people with urticaria also experience angioedema, which is deeper swelling typically occurring around the eyes, lips, genitals, hands, or feet. Unlike the surface itch of hives, angioedema can feel painful, tight, or tingling. Symptoms can vary; acute urticaria appears suddenly and clears up quickly, whereas chronic urticaria involves wheals that recur daily or almost daily for more than six weeks.

Diagnostic Methods

Clinicians primarily diagnose urticaria based on a physical examination and a detailed medical history. The doctor will ask about recent illnesses, medication use, food intake, and exposure to potential allergens. For acute urticaria, extensive testing is rarely needed unless an allergy is strongly suspected. In such cases, skin prick tests or specific blood tests (IgE) may be used to identify allergic triggers. For chronic urticaria, doctors may order basic blood tests (such as a Complete Blood Count, Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate, or Thyroid Stimulating Hormone test) to rule out underlying systemic conditions or infections. Challenge tests may be performed to confirm physical urticaria, where the skin is exposed to a suspected trigger like ice (for cold urticaria) or pressure.

Differential Diagnosis

It is important to distinguish urticaria from other conditions that cause skin rashes. It is often confused with insect bites, contact dermatitis (reaction to irritants like poison ivy), or erythema multiforme. Urticarial vasculitis is a related but distinct condition where the wheals last longer than 24 hours, are often painful rather than itchy, and leave a bruise-like mark behind; this requires a skin biopsy for differentiation. Anaphylaxis is a severe, life-threatening allergic reaction that may start with hives but includes respiratory distress, which distinguishes it from simple urticaria.

Treatment and Management

Medications and Medical Management

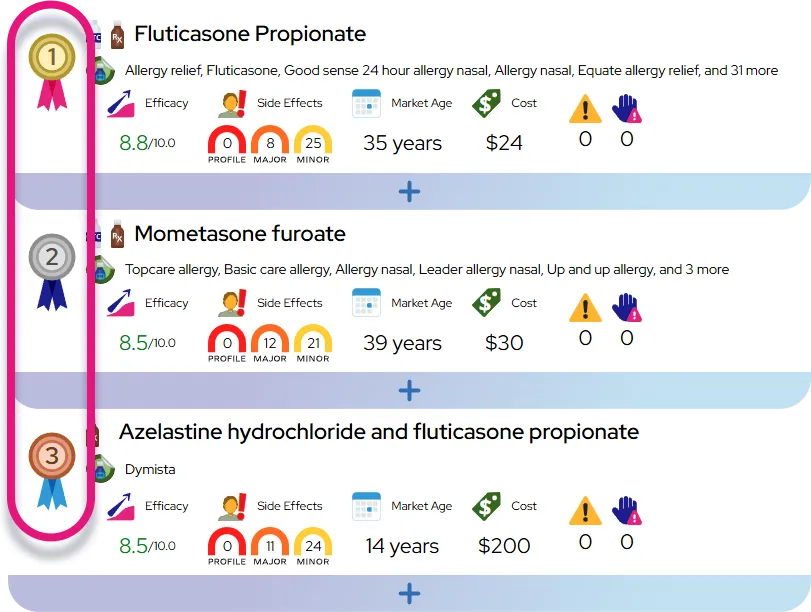

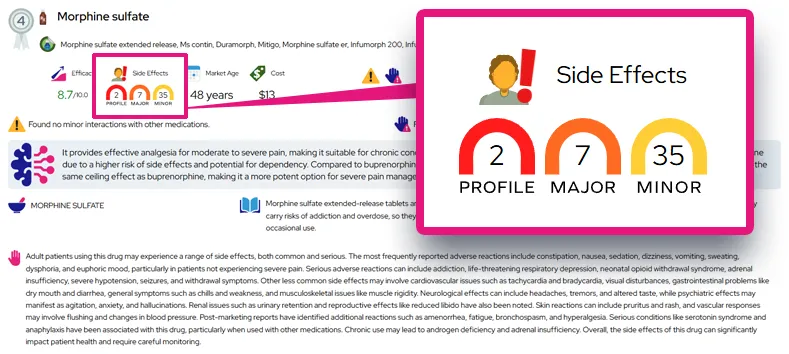

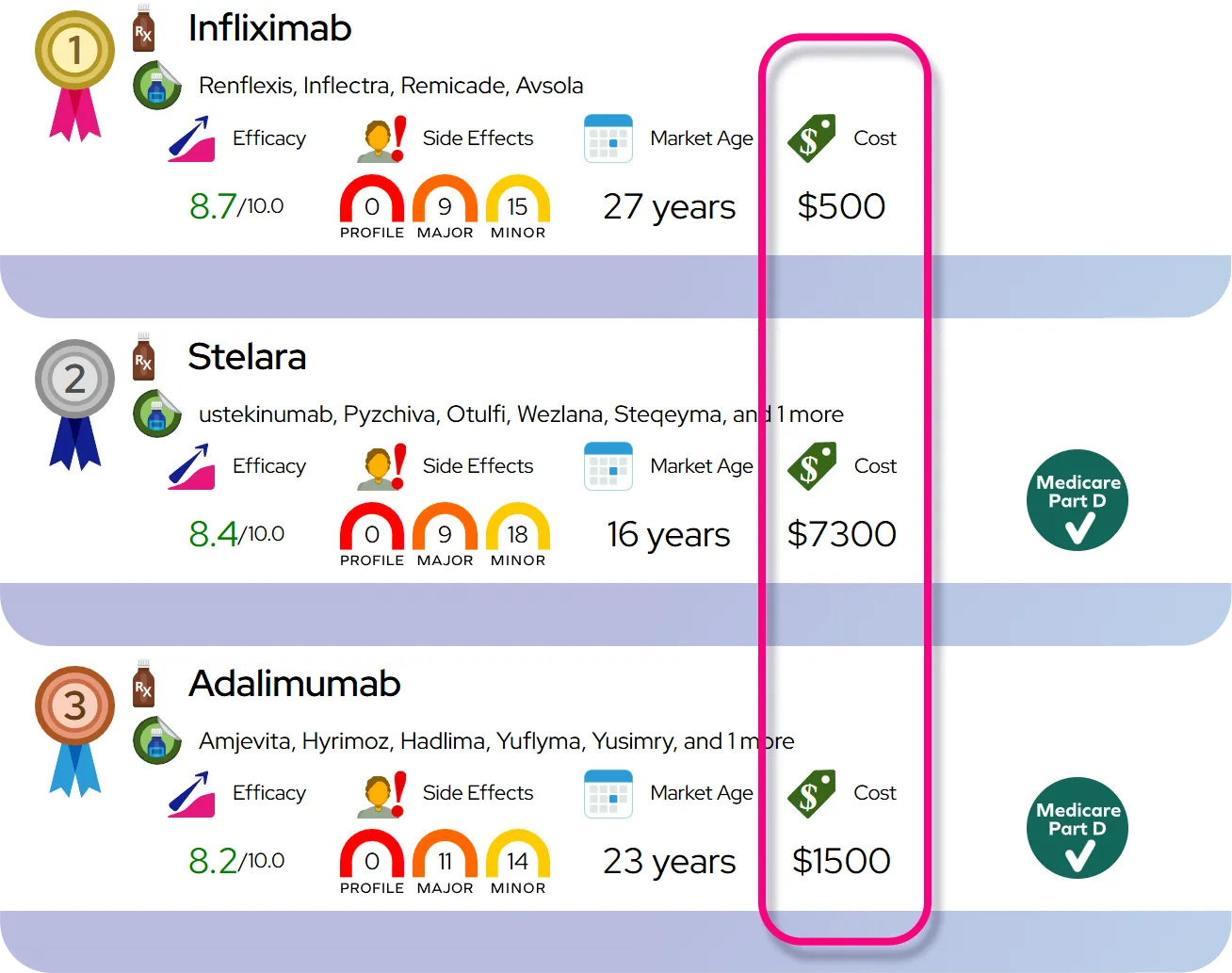

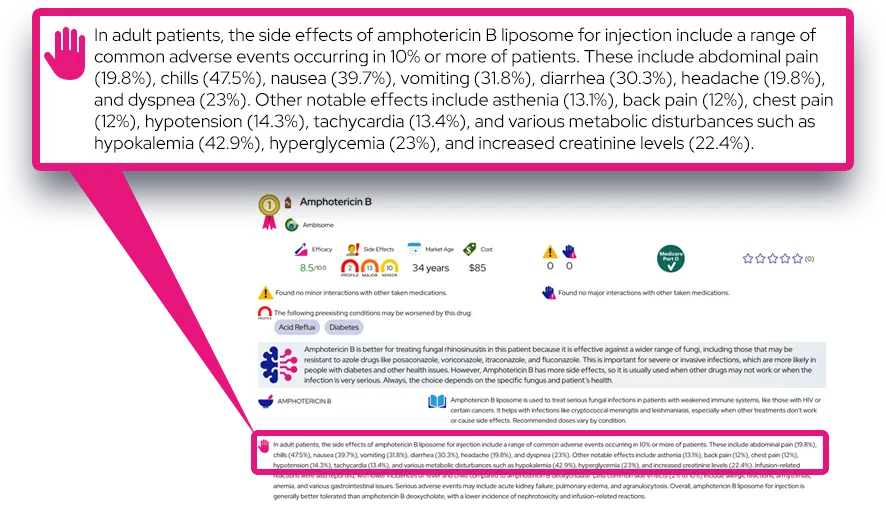

The primary treatment for urticaria focuses on relieving symptoms, particularly itching. Non-sedating, second-generation H1 antihistamines (such as cetirizine, fexofenadine, or loratadine) are the first-line therapy. These are preferred over older antihistamines because they are effective and cause less drowsiness. If standard doses are ineffective, a doctor may increase the dosage significantly under medical supervision. For severe acute flares, a short course of oral corticosteroids may be prescribed to reduce inflammation rapidly, though long-term use is avoided due to side effects. For chronic urticaria that does not respond to high-dose antihistamines, biologic therapies like omalizumab (an injectable medication that targets IgE antibodies) or immunosuppressants like cyclosporine may be recommended. These modern treatments have significantly improved outcomes for patients with refractory disease.

Lifestyle and Self-Care

Managing urticaria also involves practical self-care strategies. Wearing loose-fitting, lightweight clothing can reduce irritation and pressure on the skin. Applying cool compresses to the affected areas can soothe itching and reduce swelling. It is advisable to avoid known triggers, such as hot showers, spicy foods, or alcohol, if they worsen symptoms. Using mild, fragrance-free soaps and moisturizers can help maintain the skin barrier and reduce sensitivity. Stress management techniques are also beneficial, as emotional stress can exacerbate the condition.

When to Seek Medical Care

While most cases of hives are not dangerous, certain signs require medical attention. You should see a doctor if symptoms persist for more than a few days, if the hives continue to recur for weeks (indicating chronic urticaria), or if the itching is severe enough to prevent sleep. Emergency medical care is necessary if the hives are accompanied by signs of a severe allergic reaction (anaphylaxis), such as difficulty breathing, wheezing, tightness in the chest, swelling of the tongue or throat, dizziness, or fainting. Routine follow-up is important for chronic cases to monitor treatment efficacy and adjust medications as needed.

Severity and Prognosis

Severity and Disease Course

Urticaria ranges from mild cases with a few transient wheals to severe forms with widespread hives and debilitating itch. The condition is classified by duration: acute urticaria lasts less than six weeks, while chronic urticaria persists for more than six weeks. Acute cases are often isolated incidents that resolve completely once the trigger is removed or the infection clears. Chronic urticaria can be unpredictable; symptoms may wax and wane, with periods of remission followed by flare-ups. The course of chronic urticaria varies, but studies suggest that about half of patients see their symptoms resolve within one year, though for some, it may persist for several years.

Complications and Long-Term Effects

The condition is rarely life-threatening on its own, provided there is no anaphylaxis. However, the primary complication is the significant impact on quality of life. Chronic itching can lead to sleep deprivation, fatigue, and difficulty concentrating. Persistent visible rash can cause emotional distress and social isolation. Angioedema, if present, can be painful and temporarily disfiguring. Urticaria typically does not damage other organs or systems and does not affect life expectancy. However, chronic urticaria is sometimes associated with other autoimmune conditions, such as thyroid disease or vitiligo, so monitoring for these associations may be part of long-term care.

Prognosis Factors

The prognosis is generally favorable. Acute urticaria almost always resolves without long-term issues. In chronic cases, the prognosis is better for those without concurrent angioedema or autoimmune thyroid disease. Early diagnosis and appropriate management with modern therapies like biologics can induce remission and prevent the condition from interfering with daily life.

Impact on Daily Life

Impact on Daily Activities and Mental Health

Living with urticaria, especially the chronic form, can be challenging. The intense itching and physical discomfort can interfere with work, school, and hobbies. Sleep disturbance is a major issue, leading to daytime fatigue and reduced productivity. The unpredictability of flare-ups can make planning social activities difficult. Visually apparent hives can lead to self-consciousness, anxiety, and social withdrawal. Patients may feel frustrated if a cause cannot be found, which is common in chronic spontaneous urticaria. Coping strategies include building a support network, strictly adhering to medication schedules to prevent flares, and educating family and colleagues about the non-contagious nature of the condition.

Questions to Ask Your Healthcare Provider

To better manage your condition, consider asking your doctor the following questions:

- What is the likely cause of my hives, or is it idiopathic?

- Do I need allergy testing to identify specific triggers?

- Are there any foods or medications I should strictly avoid?

- What are the potential side effects of the antihistamines or other medications prescribed?

- Is my condition acute or chronic, and how long might it last?

- What is the plan if the current medication does not stop the itching?

- When should I use an epinephrine auto-injector (EpiPen), and do I need a prescription for one?

- Are there any lifestyle changes that could help reduce the frequency of my flare-ups?

Common Questions and Answers

Q: Is urticaria contagious?

A: No, urticaria is not contagious. You cannot catch it from someone else, nor can you spread it to others.

Q: Can stress cause hives?

A: Yes, emotional stress is a well-known trigger that can cause hives to appear or worsen existing symptoms in many people.

Q: Do I need to change my diet if I have chronic hives?

A: Usually, no. Unless a specific food allergy has been identified as a trigger through testing or history, dietary changes rarely cure chronic hives. However, some people may find that reducing pseudo-allergens (like certain preservatives) helps, but this should be discussed with a doctor.

Q: Will my hives ever go away permanently?

A: Acute hives typically go away within days or weeks and may never return. Chronic hives often go away on their own eventually, although this can take months or even years. Treatment effectively controls symptoms in the meantime.

Q: Are hives a sign of a serious internal disease?

A: In the vast majority of cases, hives are not a sign of a serious internal disease. While they can rarely be associated with autoimmune conditions or infections, they are usually a skin-limited issue.