Vertigo

At a Glance

How It Affects You

Vertigo is a condition characterized by a specific type of dizziness where an individual feels a false sensation of movement, such as spinning or swaying, even when they are stationary. This sensation typically originates from problems in the inner ear or the brain, disrupting the vestibular system which controls balance and spatial orientation. Consequently, the condition can lead to physical instability and a higher risk of accidents.

- Vertigo causes a distinct spinning or rotating sensation that affects the head and perception of the environment.

- It frequently leads to nausea, vomiting, and abnormal, jerky eye movements known as nystagmus.

- The loss of balance associated with vertigo increases the risk of falls and makes walking or standing difficult.

Causes and Risk Factors

Causes of Vertigo

Vertigo is primarily caused by issues in the inner ear, known as peripheral vertigo, or problems in the brain, known as central vertigo. The most common cause is Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV), where tiny calcium crystals in the inner ear become dislodged and float into the semicircular canals, disrupting balance signals. Other common biological mechanisms include inflammation or infection of the inner ear, such as vestibular neuritis or labyrinthitis. Meniere's disease, which involves a buildup of fluid in the inner ear, is another frequent cause. Less commonly, central vertigo is caused by conditions affecting the brainstem or cerebellum, such as migraines, strokes, multiple sclerosis, or tumors. Head or neck injuries can also trigger vertigo symptoms.

Risk Factors and Triggers

Several factors increase the likelihood of developing vertigo. Age is a significant risk factor, as inner ear structures can degenerate over time. Women are slightly more likely than men to experience conditions like BPPV. A history of ear infections, high stress levels, and the consumption of alcohol can serve as contributors or triggers. Certain medications, particularly those that affect blood pressure or ear function, may also increase risk. For those with vestibular migraines, triggers can include specific foods, bright lights, or hormonal changes.

Prevention Strategies

Primary prevention of vertigo is often difficult because many causes, like BPPV or viral infections, occur spontaneously. However, managing risk factors can help reduce the likelihood of central vertigo; this includes controlling high blood pressure, diabetes, and cholesterol to prevent strokes. To reduce flare-ups or progression in conditions like Meniere's disease, doctors may recommend a low-salt diet and avoiding caffeine or alcohol. Preventing head trauma through safety measures, such as wearing helmets during risky activities, can also prevent vertigo caused by injury. When prevention is not possible, focusing on fall prevention in the home is crucial to avoid secondary injuries.

Diagnosis, Signs, and Symptoms

Signs and Symptoms

The hallmark symptom of vertigo is the perception of motion when one is stationary, often described as spinning, tilting, swaying, or being pulled in one direction. This sensation is distinct from general lightheadedness or faintness. Clinically meaningful symptoms often include nausea, vomiting, and a loss of balance or unsteadiness. Many patients experience nystagmus, which is an involuntary jerking or rapid movement of the eyes. Depending on the underlying cause, additional symptoms may include hearing loss, a feeling of fullness in the ear, or tinnitus (ringing in the ears). In cases related to migraines, patients may also have sensitivity to light and sound.

Diagnostic Tests and Exams

Clinicians identify vertigo and its cause primarily through a physical exam and medical history. The Dix-Hallpike maneuver is a common screening tool where the doctor carefully moves the patient's head into specific positions to observe eye movements; this helps diagnose BPPV. Hearing tests (audiometry) are used to check for Meniere's disease or other auditory problems. To evaluate the vestibular system, doctors may use electronystagmography (ENG) or videonystagmography (VNG), which measure eye movements in response to balance stimulation. If central vertigo is suspected, imaging tests like Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) or Computed Tomography (CT) scans are used to rule out strokes, tumors, or other brain abnormalities.

Differential Diagnosis

Vertigo is often confused with other forms of dizziness, such as presyncope (feeling faint) or dysequilibrium (loss of balance without spinning). Doctors work to distinguish true vertigo from dizziness caused by low blood pressure, dehydration, anxiety disorders, or heart conditions. Accurately distinguishing between peripheral causes (inner ear) and central causes (brain) is critical for effective treatment.

Treatment and Management

Medical Treatment and Procedures

Treatment for vertigo depends heavily on the underlying cause. For Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV), the most effective treatment is often the canalith repositioning procedure, such as the Epley maneuver, which moves dislodged crystals back to their correct position in the inner ear. If the cause is infection or inflammation, doctors may prescribe corticosteroids, antibiotics (if bacterial), or antivirals. Medications such as antihistamines, anticholinergics, or benzodiazepines are frequently used to suppress acute symptoms of spinning and nausea, though they treat the symptoms rather than the cause. In cases of Meniere's disease, diuretics may be prescribed to reduce fluid retention in the ear.

Therapy and Lifestyle Management

Vestibular rehabilitation therapy (VRT) is a specialized form of physical therapy designed to train the brain to compensate for balance deficits. This is particularly helpful for chronic vertigo or recovery after inner ear infections. Lifestyle strategies involve moving slowly when standing up, sleeping with the head slightly elevated, and avoiding sudden head movements. Managing stress and staying hydrated can also help reduce the severity of attacks for some conditions. Modern management emphasizes keeping patients active rather than prescribing prolonged bed rest, as activity helps the brain adapt.

When to See a Doctor

While many cases of vertigo are benign, certain red-flag symptoms require immediate medical attention. You should seek emergency care if vertigo is accompanied by a sudden, severe headache, double vision, trouble speaking, weakness in an arm or leg, or difficulty walking, as these may indicate a stroke. Medical advice should also be sought if vertigo is persistent, recurrent, or accompanied by hearing loss or high fever. Routine follow-up is recommended if symptoms worsen despite treatment or if episodes interfere with daily activities.

Severity and Prognosis

Severity and Disease Course

The severity of vertigo can range from a mild, fleeting annoyance to a debilitating condition that prevents normal functioning. BPPV typically produces intense but brief episodes of spinning lasting less than a minute, whereas vestibular neuritis can cause severe, constant vertigo lasting for several days. Meniere's disease often presents with episodic attacks that can last for hours. Most forms of peripheral vertigo are acute and self-limiting or resolve with treatment, but conditions like Meniere's can be chronic and progressive over time.

Complications and Long-Term Effects

The most significant complication of vertigo is the risk of falls, which can lead to fractures and other serious injuries, particularly in older adults. Persistent vertigo can also lead to secondary anxiety or depression due to the fear of triggering an attack. While vertigo itself does not typically damage other organs, the underlying causes, such as a stroke or tumor, carry their own long-term health risks. Generally, vertigo does not directly shorten life expectancy, but the consequences of falls can be severe.

Prognosis

The prognosis for most patients is excellent. Conditions like BPPV are easily treated, though recurrence is possible. Vestibular neuritis usually heals completely, although some people may experience lingering unsteadiness. Early diagnosis and participation in vestibular rehabilitation significantly improve outcomes and speed up recovery. Even in chronic cases, management strategies allow most individuals to maintain a good quality of life.

Impact on Daily Life

Impact on Activities and Mental Health

Vertigo can significantly disrupt daily routines. During an active episode, tasks like driving, working, or even walking safely become dangerous or impossible. The unpredictable nature of attacks can lead to anxiety and social withdrawal, as individuals may fear experiencing dizziness in public. Functional limitations may require temporary adjustments at work or school, such as avoiding screens or machinery. Coping strategies include using a cane for stability, installing grab bars in the bathroom, and arranging for transportation during active periods. Support groups and counseling can be beneficial for dealing with the emotional toll of chronic balance issues.

Questions to Ask Your Healthcare Provider

- What is the specific cause of my vertigo, and is it related to my inner ear or brain?

- Can you demonstrate the Epley maneuver or other exercises I can do at home?

- Are there specific triggers, such as foods or activities, that I should avoid?

- How long do you expect these symptoms to last, and will they come back?

- Is it safe for me to drive or operate machinery in my current condition?

- Should I see a specialist, such as an ENT or a neurologist?

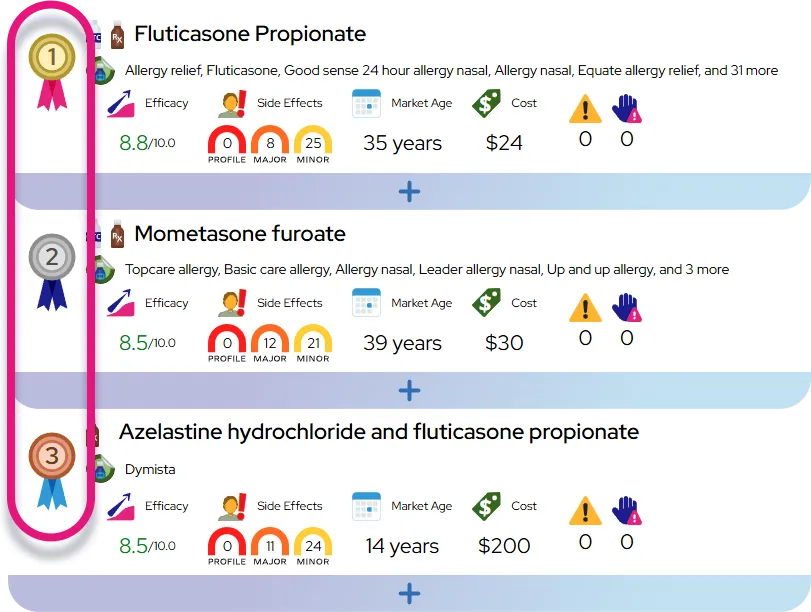

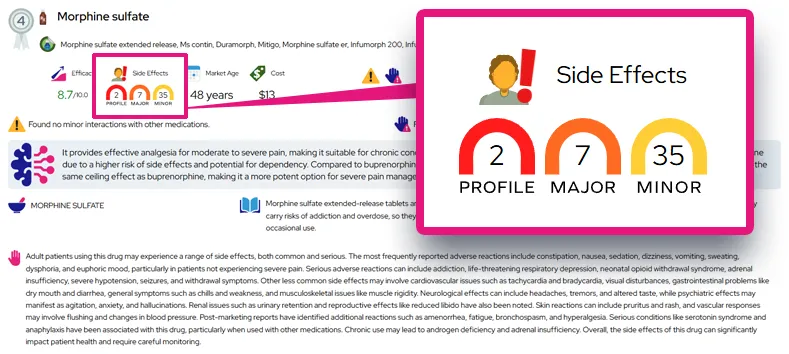

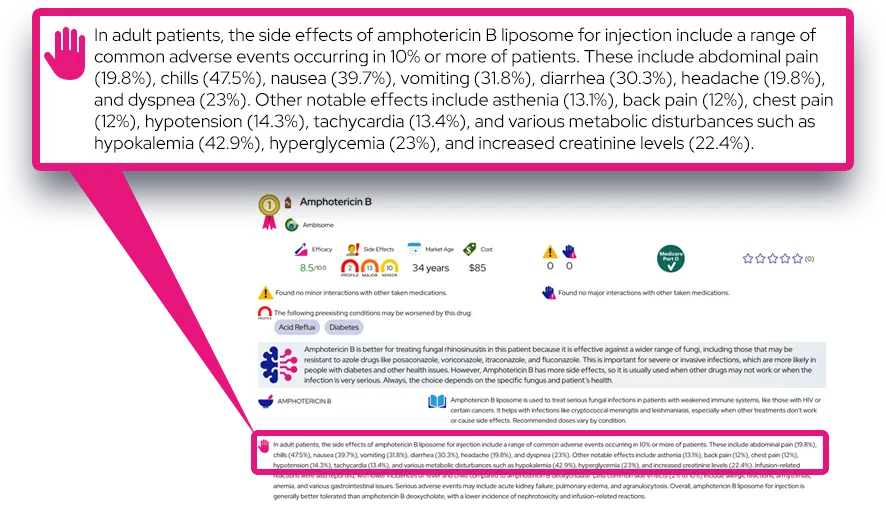

- What are the side effects of the medications prescribed for my dizziness?

Common Questions and Answers

Q: What is the difference between dizziness and vertigo?

A: Dizziness is a general term that can mean feeling lightheaded, faint, or unsteady, whereas vertigo is a specific type of dizziness describing a false sensation that you or your surroundings are spinning or moving.

Q: Can vertigo be cured permanently?

A: Many causes of vertigo, such as BPPV or ear infections, can be cured or resolved completely, though some chronic conditions like Meniere's disease cannot be cured but can be effectively managed to minimize symptoms.

Q: Is vertigo a sign of a stroke?

A: Vertigo can be a sign of a stroke, especially if it occurs suddenly alongside other symptoms like double vision, slurred speech, weakness, or severe coordination problems, but most cases are caused by less serious inner ear issues.

Q: Can I treat vertigo at home?

A: Certain types of vertigo, particularly BPPV, can often be treated at home using specific head movements like the Epley maneuver, but you should consult a doctor first to ensure you are performing the correct exercises for your specific condition.

Q: How long does a vertigo attack usually last?

A: The duration varies significantly by cause; BPPV episodes typically last less than a minute, Meniere's attacks may last several hours, and vertigo from viral infections can persist for days or weeks.